by Dr Nikesh Parekh Public Health Medical Associate and CDOP Chair, Royal Borough of Greenwich and GP, Seaford Medical Practice.

Neonatal deaths represent 42% of all child deaths in England. These deaths are not inevitable, but while many countries are making progress in this area, England’s neonatal and infant mortality rates have stagnated in the last decade. This is particularly troubling because maternal and infant health outcomes are often considered a reflection of the strength, quality and inclusiveness of any healthcare system.

Comprehensive and high-quality maternal care is imperative for neonatal health. Therefore it is also imperative, by extension, to the Government’s ambition to achieve a 50% reduction in maternal and neonatal deaths by 2025 (as set out in the NHS Long Term Plan).

An impossible choice

But there is a major barrier to this ambition: some of the most vulnerable pregnant women are afraid of accessing antenatal care because they might be charged for it. In 2017, an amendment to the overseas visitor charging regulations meant that pregnant women who are not ‘ordinarily resident’ in England are charged for their maternity care at 150% of the national tariff. Should a debt be unpaid for more than 2 months and have a value of £500 or greater, the NHS trust providing care is obliged to share the patient’s details with the Home Office – potentially leading to immigration enforcement measures.

An audit from one NHS trust showed that in one year, nearly 1 in 12 pregnant women booking with the trust were sent letters of potential charge. This policy captures undocumented migrants, refused asylum seekers, and visa over-stayers – who may be living on a low income or destitute. These women are subsequently faced with a choice: they can have some amount of care, potentially pushing them and their family into poverty; they can have a termination, which is also chargeable; or they can try to navigate the system to secure an applicable exemption – enduring the stress that goes with that, and with no guarantee of success. Many of these women have poor health literacy, so without clear signposting to support services and the time to seek this support, they are deterred from accessing the care they need.

Better data, better outcomes

This is a grim situation, but it is made more grim by the fact that we have very little information on the impact it is having on neonatal and maternal health. There is no routine data collection in England that covers this gap. Deaths are extreme cases, and represent just the tip of the iceberg – though several maternal deaths have been recorded by MBRRACE-UK. Until earlier this year, there was no data collection on the policy’s impact on neonatal and infant deaths or morbidity.

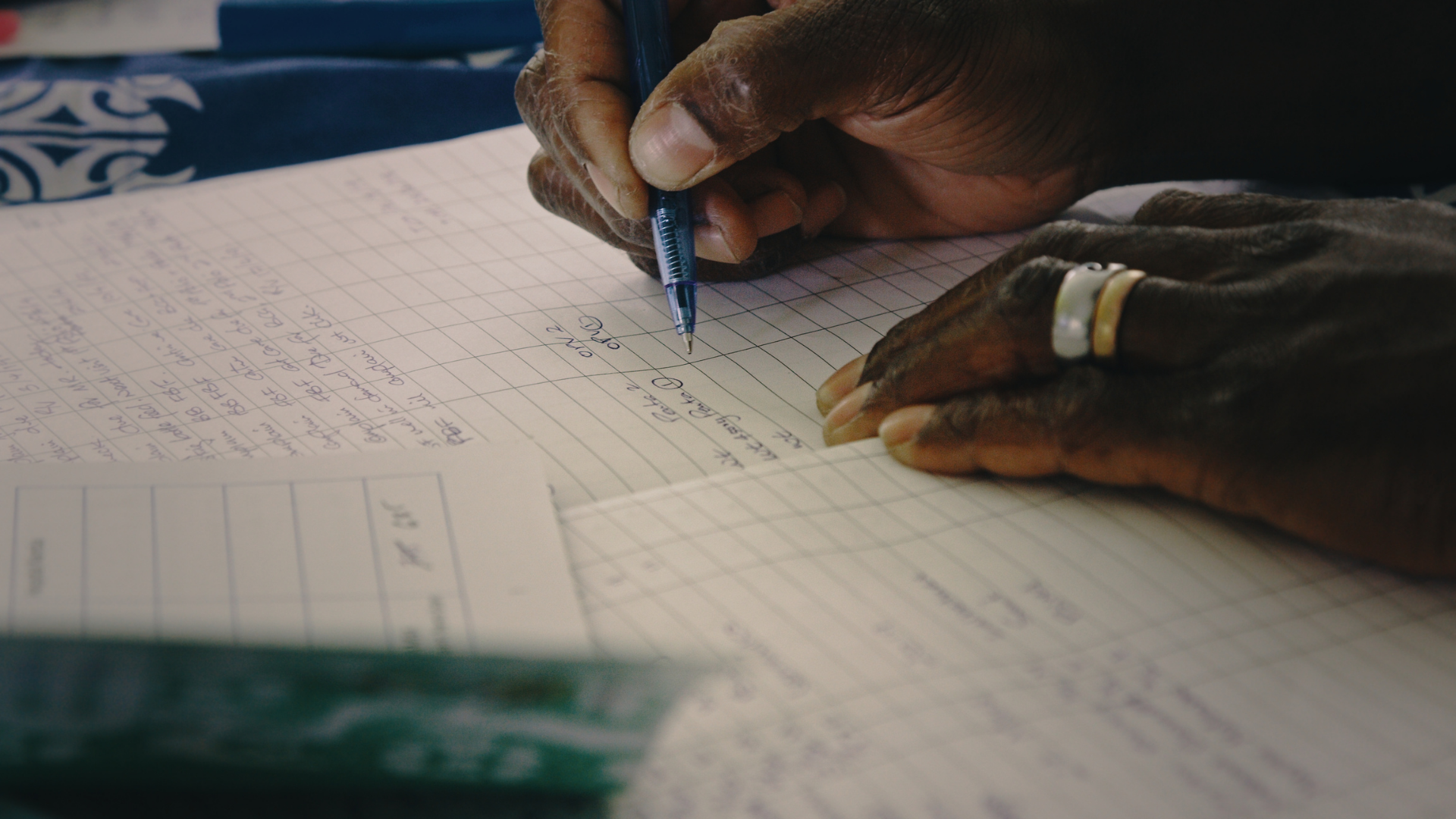

This changed thanks to the efforts of the National Child Mortality Database (NCMD). Since April, child death overview panels (CDOPs) have had the opportunity to document whether maternal NHS charging has potentially been a barrier to accessing care when reviewing a child death. This data can only be as strong as the efforts made to gather it, and many CDOPs go to great lengths to record whether a mother has been identified as chargeable, which sadly is not openly shared with maternity staff (and usually sits in the local NHS trust’s overseas visitors team).

Extraordinarily there is no visible local, regional or national governance over the policies used by NHS trusts to implement the legislation. CDOPs therefore have the unique opportunity to use their statutory position to scrutinise local implementation of the legislation, and remind the overseas visitors team (which usually sits within the finance department) that the guidance clearly states:

No one must ever be denied, or have delayed, maternity services due to charging issues. Although a person must be informed if charges apply to their treatment, in doing so they should not be discouraged from receiving the remainder of their maternity treatment.

The issue of maternal NHS charging has been further highlighted through the efforts of charity Maternity Action, who shone a light on the problems mothers are facing in their report Breach of Trust, subsequently being covered by Newsnight and the Guardian. Along with the Royal College of Midwives, they have produced guidance on Improving access to maternity care for women affected by charging which CDOPs can request their local NHS trust to adopt as damage limitation.

Taking action

The 2017 amendment to charging regulations to include maternity care propagates the stark socioeconomic inequality in child deaths in England as reported this year by the NCMD. Whilst such legislation remains in place, the Government’s ambition to halve maternal and neonatal mortality rate by 2025 will remain far out of reach.

But the work of CDOPs across the country to seek data on maternal NHS charging with every neonatal death is a ray of hope, and is making a tangible difference – we must continue and develop this important contribution. We must also use our unique position to scrutinise the local policies of our NHS trusts to ensure they do not contravene national guidance, and to ensure that considerable effort is made to identify women that do not meet exclusion criteria prior to sending them correspondence about potential charge.

To reduce the incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes, CDOPs have a role in demanding a better charging process led by the NHS trust. A process that is compassionate: not pursuing debts when the patient is without funds, offering slow repayment plans, and avoiding the use of debt collection agencies. A process that is clear, with accurate translations on all correspondence. And a process that is supportive, with clear signposting to support services such as the charity Maternity Action.

The stress of interpreting the legislation and guidance and identifying exclusions should be taken on by the overseas visitors team implementing the charges – never the patients.

Back to: Home | All publications