by Liam Walsh, author and bereaved parent

The radio is cheerily reminding me that it is the most wonderful time of the year. That hearts will be glowing when loved ones are near. That kids will be jingle belling and everyone telling I’ll be of good cheer.

As bereaved parents – and particularly around Christmas, birthdays and other anniversaries – we may be more sensitive. We may be more unpredictable. Or even more sensitive and unpredictable, you might quietly think. What I need from one person one day might be the opposite of what I need from someone else the next day. And even then, we are all different.

It is a difficult situation for you.

So good luck.

I’ll generalise. We don’t want to do Christmas. Or Christmas. It’s not really something to celebrate. It’s not a merry Christmas. We endure it. The forced jollity is one thing, our empty chair, the palpable sense of loss, an unused stocking, is quite another.

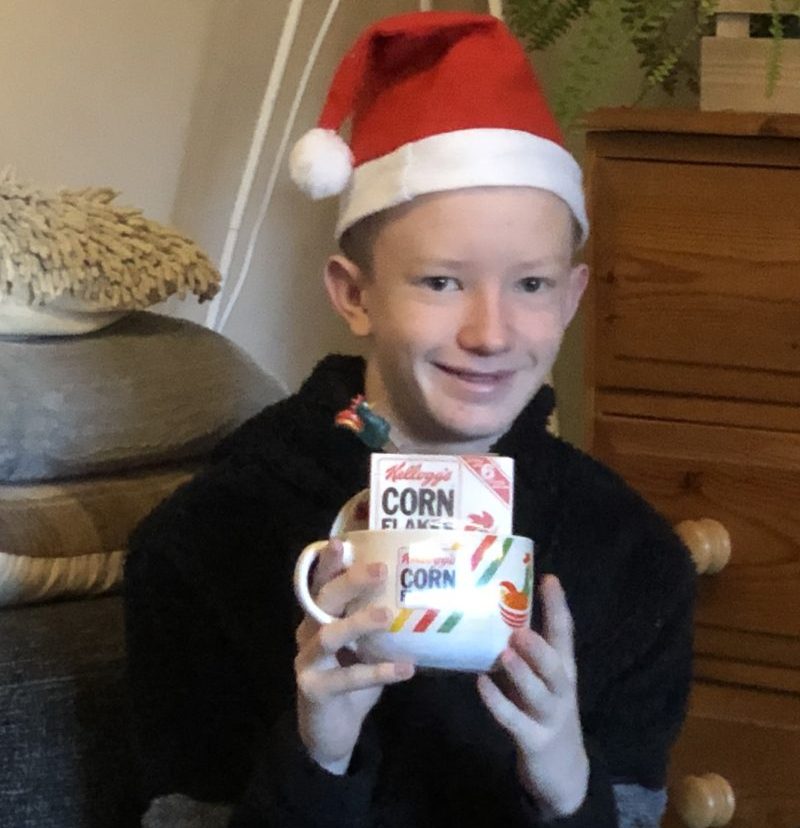

I’m a bereaved parent because my son Patrick collapsed and died suddenly in Marylebone as he was walking to the station to catch the last train home after a night at football. He was 15, with a zest for life and sparkling with teenage cheekiness. There were no indications of him being ill. That day, I was only concerned that his choice of coat would not withstand the winter storm. Patrick’s is one of 10 deaths of 4–17-year-olds in 2020 which remains officially unexplained.

He just died.

A sudden, unexpected death in childhood.

Happy Christmas your arse, as the Pogues most poetically put it.

But there are ways that you can help us to navigate the season, whether you’re a lifelong friend, work colleague or supporting professional.

Primarily, we are eager that our child is not forgotten. That the beautiful memories we created with them are preserved, shared and gently nurtured through the passing of time. True for all days for sure, but at Christmas, on birthdays and anniversaries there is a keenly desperate edge to our longing.

So, when you talk to us, acknowledge our situation and don’t fuss about saying ‘the wrong thing’. Trust me, any words, however clumsy, prove your intent. You’ve tried. No words, quite obviously, don’t. Hence, say something.

I think you’ll find it easier to do it right at the start of our conversation. To put it out there. Then you can read the room and proceed gently. Please say their name. If instead you start talking about last night’s telly, while wondering whether you should um, actually say something, you’ll feel awkward. And probably, so will I. So do it. Jump in and acknowledge. I haven’t seen you since your child died, I am so sorry for you. I know this is a tough time of year for you. There are some starters. You can breathe now and perhaps be guided by my response. If I close you down and respond about that television programme, I’m still genuinely grateful that you’ve acknowledged. I won’t forget your words, and I’ll likely come back to them with you another time. If I open the conversation up, please try to be normal.

If I may be more directive.

Don’t make it about you.

Don’t make it about the causes, or the science.

Don’t say I’m sorry to bring this up, or I didn’t want to remind you. Our loss is always present within us, part of our very essence.

Don’t say everything happens for a reason.

Don’t say was it drugs?

Don’t say I’m praying for you. Of course, you’re welcome to and I respect that. But it doesn’t help me.

Mostly though, thank you for acknowledging. Be human. Give hugs. Please don’t hide behind your personal norms. I’m a professional! I’m not a hugger! This isn’t about you, remember. So cast aside the guarded formalities and just do it.

We have a mantra: “everyone has their own worst thing” – for it is perfectly natural in conversation to match difficult circumstances – and after all, as bereaved parents we still need to live and exist in the real world. We still need to hear other people’s good news, the development and life journeys of their own children, the bad stuff too. But it needs to be appropriate. Please do not equate the stress of your Christmas parcels being delivered late with our family facing another festive season without our son, brother, grandson.

More positively, for each of these difficult examples, there are corresponding organisations, life-affirming moments and memories of sweetness to cherish.

Those simple unexpected tiny actions and words from half-forgotten friends which take our breath away.

The furtive Covid visit to our Oxfordshire garden to explain the post-mortem by the paediatrician on duty when Patrick died and the fabulous senior sister from the family liaison team in London.

Charities.

Research projects. Their minimising of future occurrences.

Support groups. Like the bereaved parents’ clubs nobody wants to be in, but nurture deep friendship.

A friend sending a picture from a shared and meaningful place.

A video of a concert that Patrick would have enjoyed. That his friend thought of him in capturing the moment, and then shared it with me, telling me what they would have discussed overwhelmed me with gratitude.

It doesn’t have to be spectacular gesture. If you send Christmas cards, include their name or a message. If you don’t send cards, send a message, make a call – do something. And if you can, sit down with us a moment. Give us the gift of your time and attention.

The most wonderful time, of the year?

Today we went to an annual festive memorial service organised by a fantastic local charity offering palliative care. Their theme was ‘time’ and speakers shared evocative, inspiring stories: of the 95-year-old still musically active, of families using that precious end of life to reflect, hold hands and to reaffirm love.

I’ve no doubt that these are honest and memorable examples, but they didn’t speak to us. They didn’t speak of the brutal immediacy that death can bring, the unfathomable processes to follow, the impersonal professionals employed to be helping. They didn’t mention being handed a plastic carrier bag containing my child’s belongings and some photocopied information leaflets. Or that our GP has not once referred to or mentioned Patrick, never mind proactively checked in on us since the day he died. Or that the coroner sent his post-mortem to us, without the promised verbal debrief first. On Patrick’s 16th birthday.

So, if you’re a professional working with child mortality please try to walk in the shoes of those whose stories you’re not going to share in your end of year review. Think of them and the bruised realities of their Christmases. How can that impact your future practice? Can you appraise what hasn’t worked and use that to improve? Please challenge yourself not to become de-sensitised to the circumstances you are dealing with. Is that fair? Each bereaved family is unique and each encounter with an agency is meaningful for us. Again, a little personalism goes a long, long way.

And yes, don’t forget to recognise the positive experiences too. And sincerely, thank you. It’s a privilege to meet and know that there are so many special people working on our behalf.

Beyond the personal, as professionals dealing with child mortality you need to do more. I salute your expertise, integrity and passion in choosing to work in such an impossibly difficult environment. In the five years since Patrick died there have been significant and life-saving steps forward, yet yes, there’s a ‘but’ here. Whether medical specialists, police officers or research scientists we need you to dig deeper and with greater urgency. It doesn’t mean working harder or longer, it means collaborating better, accelerating improvement programmes, turning data into insight, leaving comfort zones behind. You have created a special community on our behalf – please, please deliver for us.

Christmas will always be as long as we stand heart to heart and hand in hand — Dr. Seuss

Liam is the author of Red Balloons: A Father, A Son, A Memoir published by Halcyon Publishing. A share of each book sold is donated to SUDC UK.

Thank you to both of Patrick’s parents, Liam and Kate, for sharing their story with us.